Volunteers are employees who are prepared to travel to the four corners of the world to put their experience and skills at the service of others.

A Veoliaforce volunteer is a Veolia employee who, during his or her working hours, goes on a mission on behalf of the Veolia Foundation. Previously trained in humanitarian emergencies and the use of intervention equipment designed by the Foundation, they may be in the field for several weeks or provide their expertise remotely. They leave at the request of international humanitarian organisations after a disaster or to improve the living conditions of the most disadvantaged on a long-term basis. They provide expertise in one of the Group's core businesses: Water, Energy, Waste;

The Foundation coordinates and pays for logistics and travel expenses; Veoliaforce volunteers continue to be paid as if they were working in their usual job.

What about ERUs? Veoliaforce volunteers can be made available to the French Red Cross, a long-standing partner of the Veolia Foundation, to join its Emergency Response Teams (ERU). Illustration after the September 2023 earthquake in Morocco.

Become a Veoliaforce volunteer?

Employees of the Veolia Group can apply to be included among the Veoliaforce volunteers of the Veolia Foundation by following this link (access reserved for Group employees):

For which missions?

Since its creation in 2004, the Veolia Foundation has carried out nearly 250 expert missions, both on development projects and in humanitarian emergencies. Illustrations in Pakistan, Haiti, Lebanon, Bangladesh, Myanmar...

Veoliaforce volunteers's stories

Melvin Radlo: “A captivating and formative experience”

Marie Gaveriaux: "We come back from every mission stronger than ever."

On June 6, the Ukrainian population suffered terrible floods after the destruction of the Kakhova dam. In support of the solidarity operations carried out by the Crises and Support Center (CDCS) of the Ministry of Europe and Foreign Affairs, the Veolia Foundation provided mobile water treatment units.

These units - Aquaforces 2000 - can supply up to 10,000 people, in line with humanitarian standards (20 liters per person per day). Marie Gaveriaux, a Veoliaforce volunteer, was in the field at the end of June to train Solidarités International teams in the deployment of Aquaforces. She talks about her experience.

Nathalie Vigneron-Larosa: "Combining expertise to find solutions."

The Veolia Foundation has placed its Veoliaforce experts at the disposal of Solidarités International, an NGO present in particular in Myanmar, to optimize and adapt the identified solutions to the field. Nathalie Vigneron-Larosa, a Veoliaforce volunteer who monitored the project for several weeks, explains how the project was carried out.

You undertook a Veoliaforce mission remotely, more than 8,000 km from the refugee camps in Sittwe, Myanmar. Describe how you approached the mission.

Nathalie Vigneron-Larosa: It so happens that two years ago, I worked in Veolia Environnement's Technical and Performance Department with Romain Verchère, who himself went into the field with Solidarités International. So when the Foundation called me in September 2019, the subject was not completely unknown to me - although of course I haven’t seen the reality of Myanmar for myself.

What was the mission?

NVL: This was a one-off study, estimated to last three weeks, to analyse the process and design a wastewater treatment plant where Solidarités International wanted to increase capacity. There was also an issue concerning the quality of the water discharged.

How did you organize it?

NVL: We have the advantage in the Technical and Performance Department of being fairly self-sufficient. My manager lightened my work load so that I could free up some time. This was especially important since the studies to be carried out turned out, as is often the case, to be more extensive than initially envisaged! When you start working on a topic like a wastewater treatment plant in a refugee camp, you initially feel very inadequate in terms of your skills, processes and know-how, but in the end you quickly understand the techniques employed and the challenges. The processes are rudimentary but we adapt and find solutions, often by discussing the issue with colleagues and combining our expertise.

Is it frustrating to be involved in this type of project at a distance?

NVL: No, I really liked being useful and being able to work on something so concrete while still having the comfort of having all my professional tools at my disposal and being able to continue my family life alongside. The desire to travel is naturally there, but a Veoliaforce mission at a distance is both easier to get our management to accept and it opens up the challenge to people like me with young children.

Arthur de Saint-Hubert : “Lasting emergency...”

In March 2020 Arthur de Saint-Hubert, a Veolia Foundation Veoliaforce volunteer, undertook a mission to prepare for doubling the capacity of the wastewater treatment plant in one of the camps. Explanations.

You arrived in the field as part of a development project that had begun a few months earlier...

Arthur de Saint-Hubert: Yes, and very closely monitored in the Foundation over the past year. In Rakhine State, after several bouts of violent confrontation amongst the population, the Rohingyas were displaced and now live in camps. The NGO Solidarités International, a Veolia Foundation partner, has been working in the field for several years to provide drinking water and sanitation in the Sittwe camps. Against this background other Veoliaforce missions working on the issue of sanitation preceded mine.

What was your mission?

ASH: The Sittwe wastewater treatment plant needs to double in size and be improved. However, there is no electricity: everything is done by gravity, so the height of the water is the major issue for the proper functioning of the entire system. And everything has to be robust and easy to use.

What improvement is needed?

ASH: We need to be able to treat a substantially larger volume and, in addition, improve the quality of what comes out (sludge, ash and water). In the sense of the FAO recommendations, we are not yet at a good enough level of water quality for reuse in the fields, but we are making progress. As for doubling the capacity, the work started shortly after I left.

What were the working conditions in the field?

ASH: I was quite surprised to discover long-established camps that looked more like very poor settlements than refugee camps, as is usually the case. This is undoubtedly the reality of a lasting emergency... A large proportion of the population has been there for a long time, but the people I met in the camps refused to plan ahead: they don't want to imagine themselves still there in six months’ time.

Anyway, I left France without a care in the world, even though I didn't realize the cultural distance there would be between an NGO that employs a majority of local staff in the field and the practices in a highly organized group like Veolia, where I've been working for more than ten years. For the first few days, I was like a bull in a china shop... And then I realized - and it was a real learning experience for me – that it was important to take more account of the very particular context of a humanitarian intervention in the field...

Antonella Fioravanti: "A Veoliaforce mission is a collective adventure!"

Antonella Fioravanti, who has worked as an engineer for the Veolia group since 2001, has been a Veoliaforce volunteer for more than fifteen years. She has been involved in the project undertaken in Haiti with MSF since its inception.

When did you first hear about the project?

Antonella Fioravanti: Let me see, it was a very long time ago now, during an initial meeting at Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) back in ... 2012! At the time, they were running three hospitals in Haiti and were already familiar with the principle of the biodisc, a solution they wanted to implement at the Drouillard district hospital in Port-au-Prince. Time went by, and the project remained on stand-by for some time before it was finally restarted and I arrived in 2017 for a ten-day mission. The first task was to measure the quantity of water to be treated and to characterize the pollution.

Did this first diagnostic mission lead to the designing of a treatment solution?

AF: Not immediately. There were a lot more unknowns than we had anticipated. In particular, it was impossible to visualize the flow cartography. Septic tanks had been dug all over the place, as new buildings being built to expand the hospital, and it was impossible to work out where the wastewater was coming from and going to. However, this is essential in order to be able to take relevant samples and correctly analyse what needs to be treated. So the mission took longer than expected. An MSF employee continued the analyses after my departure, which allowed us to start with reliable data.

So did you continue to follow the project remotely?

AF: Yes. I was lucky to be able to stay involved in this project from the beginning until the commissioning of the chosen solution.

Did you return in 2020?

AF: Yes, we had already remotely specified the biodisc dimensions and started the costing for the equipment required, but we had to compare our projections to the actual field conditions. The size of the biodisc can vary from single to double depending on the flow rate and capacity required. The hospital had changed over time, and the environment too. We modified the layout initially planned for the biodisc and we came back with a hydraulic profile and the list of equipment to order to install everything.

You have been involved in Veoliaforce missions in Madagascar, India, Zimbabwe and Cuba. Are there always surprises waiting for you when you arrive in the field?

AF: Yes, and there’s always an element of apprehension. You have to pay attention to everything, staying focused and not letting your attention stray. Although I have to manage, lead teams and pilot projects in my daily work at Veolia Water Technologies (VWT), I don’t take initiatives alone when I’m out in the field. We work hand in hand with our partner NGO during the mission and, back in the office, we often ask advice from colleagues who give up their own time to answer us. I turned to the VWT design office for the plans, then to a specialised engineer when it came to the pumps… A Veoliaforce mission is a collective adventure!

Merel de Wildt: "The aim of a Veoliaforce mission is to move a project forward."

Merel de Wildt, engineering project manager at Veolia Water Technologies, managed to go on a mission to Haiti between two lockdown periods in 2020. With a key word to guide her: adaptability.

You registered as a Veoliaforce volunteer just a few months before leaving for the field. How did you approach this mission?

Merel de Wildt: In fact, I waited until I was a little more available, once the children had got a little bit older, to register in May 2020 during the first lockdown. I followed the training a few months later, which gave me the opportunity to learn about the project in Haiti and to discuss the possibility of a departure in the field, which was made more complicated by the second lockdown. And I finally left for three weeks.

Have you worked on biodisc installations before?

MdeW: The biodisc is a fairly simple and rustic type of equipment, suitable for small communities, such as ski resorts for example. I had hardly ever used it in my daily work in France, but the principles of the wastewater treatment process as well as the start-up procedures remain the same. And then, as things turned out, the mission ultimately did not only concern the setting up of the biodisc system...

Why do you say that?

MdeW: We suspected that the question of how to power the biodisc system was going to be tricky. Putting in the industrial wiring required to install this type of electrical box is not a skill that is easy to find in Haiti. The installation took a lot longer than we expected. We tried to find solutions but, in the end, it took three weeks. The challenge in the end was how to properly wire the box so that the biodisc could start. The “priming” (filling the installation with water) could only take place once this issue had been sorted out.

That’s the reason you had come for, though. Wasn't that frustrating?

MdeW: Not at all: the aim of a Veoliaforce mission is to move a project forward. So we try to find solutions, we analyse the situation, we call colleagues. Fortunately, I can read electrical diagrams, so I was able to transcribe the issues. The Médecins Sans Frontières representative on site was also very involved in unblocking problems. An important step was taken once the electrical part was completed and I managed to fill the installation with water 30 minutes before my departure for the airport! At the same time, I had been able to carry out analyses on raw water and prepare the analysis protocols to be done on site so that my MSF contact, who was staying a week longer, could continue with the start-up of the process.

How did you organise your absence during the trip, both at the office and at home?

MdeW: At work, I had organized an action plan so that everyone I spoke to knew who to talk to in my absence. This is the sine qua non for going on a three-week mission. And at home, well ... I had anticipated! As soon as I registered, we agreed, with my husband, on how to organise things in the event of a mission. Becoming a Veoliaforce volunteer is a choice you cannot make alone when living with your family.

Romain Duthoit: “Waste collection has taken on a new dimension at Atar.”

Head of sorting and recovery operations in Oissel (Normandy), Romain Duthoit left for Atar at the end of 2021. After helping to identify the vehicles that would be given to the city of Atar, he trained the employees in their use and maintenance.

Was this assignment in Mauritania your first Veoliaforce assignment?

Romain Duthoit: Yes, and to be honest, I didn't become a volunteer with the Foundation to be able go to the other side of the world. My intention has always been to be part of a long-term project and, occasionally, when needed, to be able to lend a hand.

Your involvement in this project began with a helping hand...

RD: It so happens that, in my career, I have collected waste and, today, I am responsible for a sorting centre. When it came to identifying vehicles that could be given to the Atar town council to optimise waste management, I knew where in my region of Normandy I would find a loader and an Ampliroll truck (with roll-off containers) which no longer met local requirements but could still be used.

Your deployment has been delayed several times due to the health crisis. Was this wait frustrating?

RD: No, because we used this time to discuss and prepare (as best possible) the receipt of vehicles on site and the upcoming training. There was actually a lot of work to be done to convince the Atar services to accept the truck and the loader! They had, until now, only used old Mercedes dump trucks and could not picture being able to drive anything else. There were also fears about access to spare parts in the event of a breakdown. In short, we had to reassure them and explain that a few hundred kilometres away, in Senegal, the same type of vehicle was being used, that an after-sales service would therefore be possible, etc.

Were there any surprises on the ground? Good or bad?

RD: Our biggest difficulty was the language barrier. Very few Mauritanians speak French, the vast majority communicate only in Arabic. But we managed to understand each other! We had to, because they asked a lot of questions and we had to go over use and maintenance with them (lubrication, levels, filters, etc.), in particular of the loader.

How was your team at the Oissel sorting centre able to compensate for your absence?

RD: Everybody was very involved in the subject. I went to Atar but the entire team, indirectly, took part in the project. When I returned, I showed many pictures to explain what I had been doing for ten days.

What's the next step?

RD: The AIMF is leading a waste characterisation study carried out by a local design office to see what could be done in terms of recycling. Consumption patterns vary greatly from one population to another. Take, for example, paper-cardboard, it would be pointless to consider recycling it as the Mauritanians feed it to the goats! So, we are only at the beginning of the study, but waste collection has already taken on a new dimension in Atar.

Frédéric Gogien: "I have a bit of a paradoxical feeling of having received more than I gave."

As a sanitation expert at Veolia's Centre-East region operations division, Frédéric Gogien spent three weeks in Mozambique in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai. He was part of the second wave of volunteers who handed over to the Mozambicans who are now operating the Veolia Foundation's Aquaforce mobile water treatment units. Here is Frédéric's account.

You and your Veoliaforce partner were part of the second wave of volunteers who took over from another pairing of Veoliaforce volunteers. What was your role?

Frédéric Gogien: The Aquaforces were set up before we arrived. When Marie Gaveriaux and I took over a few weeks after the disaster, our aim was to secure and optimise water production, and then hand over control to local teams.

How did the training phase go?

FG: We worked with four Mozambicans who quickly became able to operate the machines independently. The challenge was to keep adapting to the context.

You were given the nickname Inspector Gadget...

FG: That's right! The young people who we were training called me Inspector Gadget. My mantra is that you have to make do with what is in the boxes so that things work as well as possible. This sometimes means being inventive. Beyond the anecdotal, you need to demonstrate real flexibility during this type of assignment. Solidarités International, our partner NGO, had no idea how long it would be able to stay. So we needed to identify a framework and an organizational method that would secure the operation of the Aquaforces and therefore water access for hundreds of people. Who would buy the consumables? Who would pay the operatives working on the units? Who would plan the involvement of such and such? If we had returned home and water production stopped, I would have viewed it as a failure. In the end, everything went miraculously well. Two NGOs followed on from Solidarités International. We left properly in the right circumstances, undertaking the handovers in the right way. I kept in contact with the teams on the ground until recently and everything is still running smoothly.

How do you go back to your daily life in France?

FG: There is the gratifying feeling of working for a group that enables me to get involved in this sort of work during work time, and then the need to readapt to a very different job to the one that we had been doing for three weeks. My post at Veolia Centre-East involves producing a lot of documents - analysis, reports and so on. In Beira, on the other hand, I was producing water!

What's your view of the assignment?

FG: I gained a lot of technical knowledge and met some really lovely people. Finally, I have the incongruous feeling of having received more than I gave.

Interview by Veolia Foundation.

Marlène Cothenet: "I was impressed by the resilience of the local population."

Marlène Cothenet has been working for Veolia since 2012 and is a water research and projects engineer. She heads the Greater Lyon Water research and projects unit and has been working there for four years, having firstly gained experience in the Centre-East regional office.

You volunteered to go to Beira in Mozambique to help the population hit by Cyclone Idai. What did this voluntary work with the Veolia Foundation actually involve?

Marlène Cothenet: The aim was to provide the most destitute people with drinking water both to meet the primary needs of those who had lost everything in the disaster and also to try to curb the expected cholera epidemic in a region where the disease is already endemic.

So you arrived on the ground as a Veoliaforce volunteer to work with a partner NGO - Solidarités International. What were your first priorities?

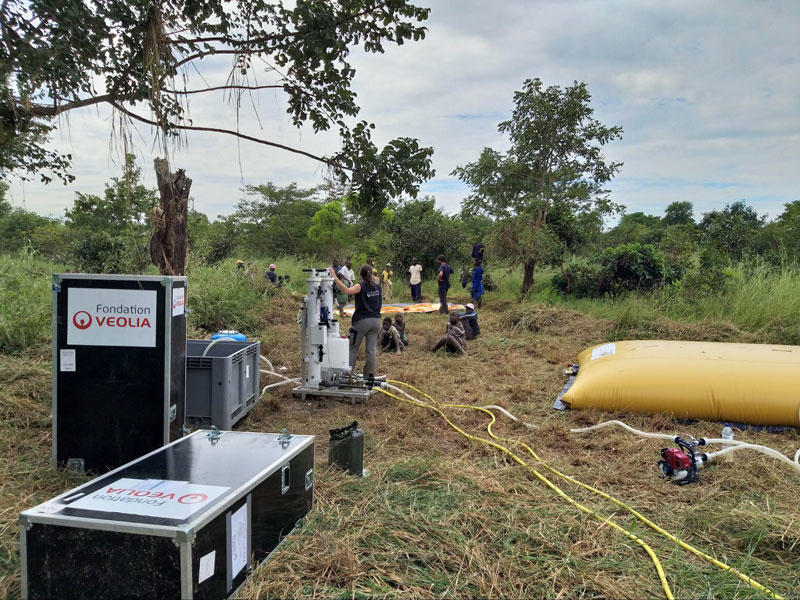

MC: Our aim was to identify the locations where the two Aquaforce 2,000 units should be deployed. These are the mobile water purification units designed by the Veolia Foundation. It proved even more difficult as the needs were difficult to assess, as the population was still on the move (the first households were returning to partially destroyed houses in urban areas, and people were arriving in the camps having left the ravaged rural areas...). I teamed up with Romain Thémereau, another Veoliaforce volunteer, and we spent several days criss-crossing the region before arriving at the village of Tica-Muda, 60km from Beira, where a camp for displaced persons had been set up. The first Aquaforce 2,000 was deployed there. The second unit was set up in the Maraza neighbourhood of Beira, which is particularly affected by cholera.

How do the Mozambicans view these newcomers from abroad?

MC: In the areas where we worked, the Mozambicans warmly welcomed the foreign workers. I was impressed by the resilience of the local population. In Beira, people quickly rallied round and started to rebuild, repair roofs and clean up the streets. The situation is more difficult for those living in rural areas. They have lost their homes and their crops, which were their means of subsistence. Their stories are quite moving.

Is the water produced using little-known equipment well received?

MC: The Mozambicans in the camps were keen to drink the water even before it was ready. We were also visited by a minister who, like us, drank the water from the Aquaforces. It was reassuring for people.

How did you communicate with the Portuguese-speaking population?

MC: I spoke Portuñol! A little Spanish and a lot of resourcefulness, coupled with the help of English-speaking Mozambicans who translated for us.

What state are you in when you return from three weeks in a humanitarian emergency context?

MC: You quickly get back into your daily routine but you obviously feel out of step at first. The time spent on the ground is intense in an emergency and survival situation far removed from our comfortable lives in France.

Interview by Veolia Foundation.

Marie Gaveriaux: "Training the local people to ensure sustainable access to water."

A chemical and process engineer at Veolia Eau, Marie Gaveriaux spent three weeks in Mozambique in April in the Beira region after Cyclone Idai wreaked havoc in the country. As a Veoliaforce volunteer, she trained local people to operate the Foundation's equipment.

You left a month after tropical Cyclone Idai made landfall. The cyclone particularly affected Mozambique's coastline. What were your first impressions on the ground?

Marie Gaveriaux: The residents have demonstrated a surprising level of resilience: the streets were quickly cleared of debris. However, the situation was significantly more challenging in the rural areas than in Beira, which is nevertheless the country's second city with a population of 500,000.

From a personal standpoint, I discovered the world of humanitarian coordination, a world that I knew nothing about. It is impossible to imagine the organizational structures put in place after this sort of disaster. And I am full of admiration for Solidarités International, the Veolia Foundation's partner, with whom we worked.

On the ground you and Frédéric Gogien took over from another pair of Veoliaforce volunteers. What was your role?

MG: Marlène Cothenet and Romain Thémereau worked with Solidarités International to set up two Aquaforce 2000 units before our arrival. We had to organise the next phase of the project. We had to optimize the quality of the water produced and above all train a team of local people to ensure sustainable water access.

How did the training go given the fact that you don't speak Portuguese?

MG: We got by with a bit of English, a bit of Spanish... and a lot of hand gestures! It was important that there were two of us. Each of us carved out a place and found a way of expressing themselves. Our trainees quickly gave Frédéric Gogien the nickname of Inspector Gadget. Our aim was to ensure that the four young Mozambicans who we were training became independent. They were starting up the Aquaforce units themselves after a few days of training.

What arrangements did you make to cover your time away from work at Veolia Water Technologies (Saint-Maurice, Val de Marne, Veolia Eau)?

MG: The timing wasn't ideal as my project manager was going on maternity leave on the very day I had to leave. But my managers were a great source of support. They gave me the go-ahead on a Sunday and we organised the handover as best as possible so that I could go away without it hitting my team too hard.

What's your view of the assignment?

MG: I headed home with the feeling of having had an incredible experience. I learned a lot about myself, the country...coming home was inevitably somewhat brutal - you have to get back in tune with reality. We spent three weeks on the ground, having to adapt every day, and sometimes improvise in order to find the best solution. You come back to a more settled and also more ordered way of life. That's the nature of the game!

Interview by Veolia Foundation.

Camille Beaupin: "The concept of time is different in humanitarian emergencies."

You were asked to go on this Veoliaforce volunteer assignment. How do you prepare for travelling to a humanitarian emergency situation?

Camille Beaupin: You obviously need to plan ahead as you will be away from both work and home, and you need to be in a position to be responsive and fly out the very next day. Once the practical arrangements have been sorted out, you can fully devote yourself to your role.

I had never worked in a post-humanitarian disaster context before, so I found arriving on the ground slightly disconcerting. Many humanitarian aid workers were on the ground and coordination is done as well as possible, but information transfer is not always perfect. I discovered what goes on "behind the scenes" in humanitarian work over the first few days. It's a job in itself - identifying needs, tailoring resources, sharing out equipment etc.

You teamed up with a permanent member of the Foundation's staff and set up an Aquaforce 2000, the mobile drinking water purification unit designed by the Foundation's engineers, working with MSF.

CB: Yes, several dozen kilometres from Dombé to the west of Beira. We needed to pinpoint the best water supply point and organise access to the distribution systems that we wanted to set up as close as possible to the local communities, i.e. 1km of piping had to be laid in the open country.

How did you get on with the local population?

CB: Because we were producing water with equipment that was unknown to the Mozambicans, we had to adopt an educational approach, drink the water from the Aquaforces, and, in a general sense, explain what we were doing. But above and beyond our work as Veoliaforce volunteers, the local communities were very dynamic, despite the tragedy that had occurred. People are resilient and are already looking to rebuild in a relatively independent way. It was impressive stuff and I did at times wonder how we would react in France if faced with this sort of disaster...

What surprised you the most during this assignment?

CB: Volunteers need to be flexible to deal with the contingencies. The situation changes every day, everyone wants to do their best but has to coordinate with the other stakeholders involved. And then you are in contact with contacts abroad, without always grasping that it is actually the weekend elsewhere in the world and decisions will only be taken on Monday. The concept of time is different in humanitarian emergencies.

Sylvain Delage: "People had nothing left in Dombé"

You left in early April as part of the second wave of Veoliaforce volunteers after Cyclone Idai hit Mozambique. What were your first impressions on the ground?

Sylvain Delage: It was both surprising because we didn't really know what to expect, yet everything also seemed quite organised. I didn't know who was going to greet me in Beira but I followed my luggage which a driver had loaded into a MSF car. This was followed by a briefing with the NGO's teams (the NGO is a Veolia Foundation partner), and then we were very swiftly on the ground. We slotted into fluid processes despite being in a humanitarian emergency context.

In Beira and then Dombé, you operated the Aquaforces, the mobile water production units designed by the Veolia Foundation, and trained staff to use them.

SD: Yes, the first wave of Veoliaforce volunteers deployed the equipment and those, like me, who came on the second wave, operated the units and prepared the Aquaforces for life after our departure. With Julien de Sousa in Beira and Camille Beaupin in Dombé, we trained MSF staff and local volunteers so that water production could continue after we all left.

You worked in an urban area in Beira and in Dombé in the rural region of Manica. What is life like for the communities hit by Cyclone Idai?

SD: Things are very different depending on the environment. Rebuilding has begun in Beira and there are lots of people in the markets, people have smiles on their faces, and their resilience is coming to the fore. The atmosphere is completely different in the rural areas. People have nothing left: they are hungry, they flag you down at the roadside, tell you about spending three days perched in the trees waiting for the water levels to go down. The climate is also more challenging and the living conditions for Veoliaforce volunteers are basic: no water or power...we had to acclimatize to it.

How did you find returning home after three weeks away?

SD: A Veoliaforce volunteer assignment is first and foremost an enormous amount of visual information to take in. The days are packed and you have to constantly pay the utmost attention. You come back to a more normal pace of life. As for me, all I need is a good night's sleep and I am ready to go! My colleagues were curious about what I had been doing for three weeks, so I prepared a report, with lots of photos, to tell them about it.

Interview by Veolia Foundation